Best New Weight Loss Drugs (2025): Top GLP-1 Efficacy, Tolerability, Pipeline/Clinical Trials

Evaluating the best new weight loss drugs on the market & in clinical development as of March 2025

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) like Semaglutide and dual mechanism GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists like Tirzepatide are highly effective treatments for obesity and all medical conditions resulting from obesity (e.g. sleep apnea, GERD, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperglycemia, etc.).

It’s not really surprising that these drugs are “treating other conditions” effectively. Some argue that they are treating these conditions as a result of direct mechanisms that are independent of fat loss — and while I’m open to this idea — unless you prove this via decoupling the effects, I think it’s unlikely.

Treating obesity is a force-multiplier. You lose body fat from an obese state, your health improves and other medical conditions miraculously “improve” or “disappear.” It’s not rocket science. And although some think recent weight loss in the U.S. is a social contagion… it’s most likely just an Ozempic contagion.

Most people don’t admit to taking these drugs. If you bring up their weight loss, you’ll say wow you look great — what have you been doing? And they’ll say: I’ve been sticking to a strict diet and exercising or something… which is probably true. But they’re not telling you that they’re taking Ozempic or whatever because why would they?

They don’t know how you’ll react. You might say “it’s not natural therefore it’s bad” or “I’ve heard it could cause cancer” or something… so it’s easier to just say yeah hard work/discipline. Suddenly everyone has “hard work and discipline” (LOL). Approx. 1 in 6 American adults are on weight loss drugs (WLDs) in 2025.

I think this is a good thing. I may make the case for Universal Basic Ozempic (UBO) because it would save the U.S. government money long-term (I think)… but need to do more research. I dislike the fact that people in the U.S. and in other countries are getting these medications on the cheap (via “compounding pharmacies”) etc.

Why? It creates a bad feedback loop for pharma. If you want more innovative drugs in the future, you should want people paying more money so pharma can throw more money into the R&D pipeline. In a socialist/cheap pharma/medical system these drugs wouldn’t exist… they likely wouldn’t have been invented.

I think these drugs are a stepping stone to an obesity vaccine and/or permanent targeted gene edits that will maintain an optimal level of body fat. I’ll write about that some other time.

READ: Gene Editing & Therapy for Obesity: Top Targets for Weight Loss & Body Fat Optimization

I. Obesity to GLP-1 Pipeline

Something not many people know is that body weight is genetic. You say “willpower”… yet willpower is genetic. You say choices… choices are a byproduct of your genetic algorithm.

And no there’s not a “single gene” implicated here. You say it’s the food environment? Well why can some (small %) of people easily resist it? Their genetic signatures.

Thankfully I’ve never been obese, but am more familiar with the diet/weight loss literature than you… and I know most people are statistically likely to regain all lost weight within ~4-5 years post-loss (usually beyond baseline so they end up even fatter).

Weight loss maintenance is difficult for formerly obese because obese people have more fat cells and different genetics — and these signal higher hunger than someone who’s never been obese (the brain is signaling extreme hunger).

So no matter what bizarre diet fad a person is using (fasting, keto, high carb, vegan, carnivore, calorie counting, etc.) — it’s irrelevant. Calories are the most important underlying variable, macro composition can modulate satiety to some extent — but not enough.

A small % of people can maintain long-term by staying focused, but most people relapse… due to genetics (brain genetics, body genetics, etc. — the entire genetic picture) and compensatory physiologic adaptations post-weight loss.

We shouldn’t want these people to die early… so it’s smart to get them on weight loss drugs (e.g. GLP-1s) until something better comes along. There may be some long-term cancer risks, but these pale in comparison to croaking within the next 5 years from a heart attack or stroke.

Global Obesity Burden. Obesity has become a critical public health challenge, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating that worldwide obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. As of the latest data, over 650 million adults are obese—a figure projected to grow in coming decades (WHO Fact Sheet). Beyond prevalence, obesity is associated with a host of comorbid conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, and certain cancers. This escalating health burden underscores an urgent need for more effective obesity management strategies.

Lifestyle to Pharmacotherapy. Traditional weight management interventions—diet, exercise, and behavioral counseling—have consistently yielded moderate or short-lived weight loss. Bariatric surgery offers more pronounced, sustained results for severe obesity, but relatively few patients meet surgical criteria or opt for it. Over the past decade, however, pharmacological treatments have evolved dramatically. Early anti-obesity medications often provided limited efficacy (~5–10% average weight loss) or encountered tolerability issues. In contrast, novel glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and related multi-agonist therapies now regularly achieve and sustain 15–20% or more average weight loss in randomized trials. Some experimental agents approach ~25% reductions—figures once considered achievable only by surgery.

Cardiometabolic Benefits. Equally important, these newer drugs confer metabolic and cardiovascular advantages. For instance, GLP-1 receptor agonists can improve glycemic control, reduce blood pressure, and lower the risk of major adverse cardiac events (NEJM: Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes). Consequently, health authorities increasingly recognize obesity pharmacotherapy not as a luxury but as an essential component of chronic disease management—paralleling approaches in hypertension or hyperlipidemia.

Paradigm Shift & High Demand. The advent of potent, well-tolerated medications like semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (ZepBound) marks a paradigm shift. Demand for these therapies already outstrips supply in some regions, indicating both the magnitude of unmet need and the challenges of ramping up manufacturing. Analysts project the global obesity drug market could surpass USD 100 billion within the next decade (Morgan Stanley Report), as more clinicians adopt these medications for long-term weight management in patients with BMI ≥ 30 or ≥ 27 with comorbidities.

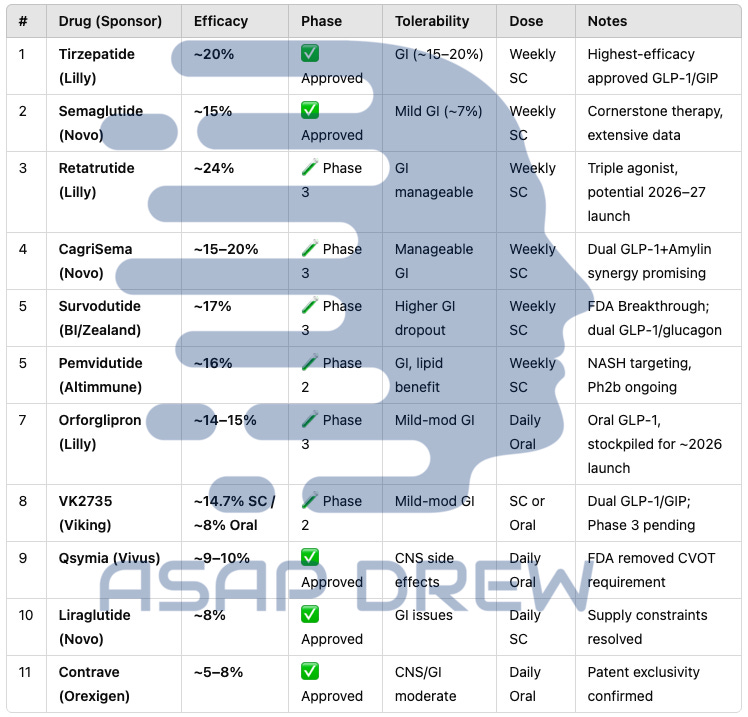

II. Most Effective Weight Loss Drugs (2025)

To rank anti-obesity drugs by efficacy, I prioritize:

Percentage of body weight loss (mean or median) at key endpoints in Phase 2 or Phase 3 clinical trials, typically over 36 to 72 weeks.

Trial design (placebo-controlled, double-blind, size and duration).

Highest approved or tested dose for each agent.

Because several investigational drugs have not completed Phase 3, some rankings use Phase 2 data. Efficacy percentages can evolve with longer follow-up. Nonetheless, these figures provide a snapshot of relative potency among approved and emerging therapies.

This is a ranking that combines drugs that were approved by the FDA (available for consumers) AND those that are still in clinical trials.

1. Retatrutide (Eli Lilly): Triple Agonist (~24.2%)

Mechanism: Simultaneous agonism of GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors (“triple incretin”).

Efficacy Data: In a Phase 2 trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine, adults with obesity receiving the highest dose (12 mg weekly) lost an average of 24.2% of their baseline body weight at 48 weeks (no plateau in sight). (NEJM Retatrutide Phase 2 Trial).

Context: This ~24% reduction is the highest reported so far in a sizable obesity trial. Some participants exceeded 30% weight loss—levels approaching bariatric surgery outcomes.

Status: Now in Phase 3. If confirmed, retatrutide may redefine “maximal medical weight loss.”

2. Tirzepatide (ZepBound, Eli Lilly): Dual GIP/GLP-1 (~20.9%)

Mechanism: A dual agonist at GIP and GLP-1 receptors, enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppressing appetite.

Efficacy Data: In the SURMOUNT-1 trial (adults with obesity), 15 mg weekly tirzepatide achieved 20.9% mean weight loss at 72 weeks

(NEJM SURMOUNT-1). About 57% of participants at the highest dose lost ≥20% of baseline weight.Approval: FDA-approved in 2023 (brand name ZepBound) for chronic weight management in adults with BMI ≥30 or ≥27 with comorbidities.

Context: Tirzepatide’s ~20% reduction set a new bar for approved drugs prior to retatrutide’s Phase 2 release. It remains the most potent anti-obesity agent currently on the market.

3. Semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy, Novo Nordisk): GLP-1 Monotherapy (~14.9%)

Mechanism: Selective GLP-1 receptor agonist that decreases appetite and caloric intake, slows gastric emptying.

Efficacy Data: The STEP 1 trial in NEJM reported 14.9% mean weight loss over 68 weeks on semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. 2.4% with placebo

(NEJM STEP 1). A subset of patients reached or exceeded 20% weight loss with continued use.Approval: Wegovy was FDA-approved in 2021, igniting significant clinical uptake.

Context: Semaglutide dramatically outperformed older oral agents, helping usher in the modern wave of effective obesity pharmacotherapy.

4. CagriSema (Cagrilintide + Semaglutide, Novo Nordisk)

Mechanism: Weekly co-formulation of a long-acting amylin analog (cagrilintide) and semaglutide (GLP-1).

Efficacy Data: Phase 2 data showed ~15.6% average weight loss by 32 weeks, outpacing each monotherapy arm (company release, Novo Nordisk). In newer trials (REDEFINE 1), the combination exceeded 20% for many participants over ~68 weeks.

Status: Entered Phase 3 in 2023. If results replicate, approval could come by 2026.

Context: Demonstrates the synergy of amylin + GLP-1. Early evidence suggests it rivals or surpasses semaglutide alone and may challenge tirzepatide’s efficacy range.

5. Survodutide (BI 456906, Boehringer Ingelheim & Zealand Pharma): Dual GLP-1/Glucagon

Mechanism: Activates GLP-1 receptor to reduce food intake and glucagon receptor to enhance energy expenditure.

Efficacy Data: Phase 2: At 46 weeks, the highest dose (4.8 mg) produced 14.9% mean weight loss in the full analysis, and up to ~18–19% in those who completed the highest-dose titration. Subset analyses suggest continued weight decline beyond 46 weeks.

Status: Advancing to Phase 3.

Context: If tolerability improves with a slower dose escalation, Survodutide might achieve near-20% losses. Its “GLP-1 + glucagon” approach is akin to tirzepatide’s “GLP-1 + GIP,” but with slightly different metabolic effects.

6. Pemvidutide (Altimmune): Dual GLP-1/Glucagon

Mechanism: Similar oxyntomodulin-based approach: co-stimulation of GLP-1 and glucagon pathways.

Efficacy Data: The Phase 2 MOMENTUM trial (48 weeks) reported 15.6% mean loss at the highest dose (2.4 mg) vs. ~2% placebo. Notable improvements in liver fat reduction and preservation of lean mass.

Status: Altimmune may initiate Phase 3 soon; a partnership for large-scale trials is anticipated.

Context: Efficacy near semaglutide levels. Could differentiate further via hepatic/lipid benefits or muscle-sparing data.

7. Orforglipron (Eli Lilly): Oral GLP-1

Mechanism: A non-peptide small-molecule GLP-1 receptor agonist taken once daily.

Efficacy Data: In a Phase 2 trial published in NEJM, the highest orforglipron dose led to ~14.7% average weight loss by 36 weeks

(NEJM Orforglipron Phase 2).Status: Phase 3 initiated. Approval could come by ~2026.

Context: The first oral therapy to approach injectable-level efficacy, overcoming prior limitations of peptide-based pills (like oral semaglutide). If safety and tolerability hold up, orforglipron could be a game-changer for needle-averse patients.

8. Viking Therapeutics’ VK2735: Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonist

Mechanism: Similar in concept to tirzepatide—agonizing GLP-1 and GIP, but still investigational.

Subcutaneous Formulation: Phase II data: ~14.7% mean weight loss after ~13 weeks (shorter trial duration than most). Dosing flexibility could allow weekly or monthly injections.

Oral Formulation: Achieved ~8.2% weight loss in a short Phase I (28 days). A Phase II trial (VENTURE-Oral) is underway, with data expected in 2025.

Context: Viking is rapidly advancing both injectable and oral versions. The subcutaneous candidate’s ~14.7% in ~13 weeks suggests it may rival orforglipron and possibly semaglutide if longer studies confirm durability.

Status: Subcutaneous is heading toward Phase III readiness (target ~Q2 2025). Oral is in Phase II.

9. Legacy/Older GLP-1 RAs

Examples: Liraglutide (Saxenda), Exenatide (Byetta), Dulaglutide (Trulicity).

Efficacy: Liraglutide 3.0 mg (Saxenda) yields ~8% weight loss over 56 weeks. Exenatide and Dulaglutide for type 2 diabetes typically yield 3–5% weight reduction.

Context: Though beneficial, they offer lower maximum weight loss and/or more frequent injections (daily for liraglutide), leaving them overshadowed by semaglutide or tirzepatide in obesity management.

10. Other Oral/Combo Drugs (Pre-GLP-1 Era)

Phentermine/Topiramate (Qsymia): ~9–10% mean loss at 1 year; limited by potential CNS/cardiovascular effects and teratogenic risk.

Naltrexone/Bupropion (Contrave): ~5–8% mean loss, variable GI or neuropsychiatric side effects.

Orlistat (Xenical): ~5% mean loss, hampered by gastrointestinal adverse effects (steatorrhea) and minimal systemic absorption.

Although these remain options, especially for those who cannot use GLP-1–based agents, their efficacy is significantly lower.

11. Setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals)

If you don’t have highly specific genetic abnormalities causing your obesity (POMC, LEPR deficiency) — this medication won’t be a good fit.

Mechanism: Melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, potent in rare genetic obesity syndromes (POMC, LEPR deficiency).

Efficacy: In patients with these syndromes, weight reductions can exceed 20–30%; in “common” obesity, it is not effective.

Context: A specialized niche treatment, not for broad obesity management.

Key Takeaways:

Multi-Agonists Leading the Pack. Triple- and dual-incretin agonists (like retatrutide and tirzepatide) now surpass 20% average weight loss—on par with lower-end bariatric surgery outcomes in some studies.

Semaglutide’s Breakthrough, then Surpassed. Semaglutide remains a cornerstone therapy (15% range), but is now eclipsed by newer combos. Still, it has a mature safety record.

Oral Formulations Poised for Impact. Orforglipron’s near-semaglutide-level efficacy could dramatically expand usage if Phase 3 data confirm safety and tolerability.

Older Drugs’ Diminishing Role. Phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, and orlistat produce modest weight loss. They may persist as niche or adjunctive treatments, but the landscape is shifting fast toward high-efficacy incretin-based regimens.

III. Tolerability & Safety Profiles

A.) Common Adverse Events Across GLP-1–Based Therapies

Mostly GI Effects. A majority of GLP-1 receptor agonists (and multi-agonists like tirzepatide or retatrutide) share a class-wide tendency to cause gastrointestinal (GI) side effects. These occur due to delayed gastric emptying and central satiety signals.

Typical symptoms include:

Nausea (often the most frequently reported)

Vomiting (particularly during dose escalation)

Diarrhea or constipation

Abdominal discomfort or bloating

These GI events are usually mild to moderate in intensity and often transient, improving as patients adapt to the medication.

Dose titration—starting with a lower dose and gradually increasing—is crucial to minimize GI intolerance.

B.) Estimated Tolerability of Key Agents

1. Semaglutide (Wegovy)

Profile: In clinical trials (e.g., STEP 1), approximately 40–44% of participants on semaglutide reported some degree of nausea; a smaller fraction (~20–25%) reported vomiting.

Discontinuation Rates: Roughly 4–7% of participants stopped therapy due to adverse events, often related to GI issues.

Long-Term Data: Accumulating real-world evidence suggests these events decrease after the initial 2–3 months if dose titration is done properly.

Reference: STEP 1 GI data: New England Journal of Medicine

2. Tirzepatide (ZepBound)

Profile: As a dual GIP/GLP-1 agonist, tirzepatide’s GI side effects are broadly comparable to semaglutide in frequency but vary with dose (5, 10, or 15 mg). Nausea (15–20%) and diarrhea (~15%) are common, with vomiting less frequent but still notable.

Discontinuation Rates: In the SURMOUNT-1 trial, about 5–7% of patients on higher doses discontinued because of GI events.

Additional Notes: Some patients report mild increases in heart rate; gallbladder-related events can occur with rapid weight loss (common to all potent agents).

Reference: SURMOUNT-1 safety: New England Journal of Medicine

3. Retatrutide (Triple Agonist, Investigational)

Profile: Early phase data show GI adverse events are dose-dependent and similar in type (nausea, diarrhea). At the highest doses (8–12 mg), a considerable proportion experienced GI side effects, but most were mild to moderate.

Management: Slow dose escalation significantly reduces discontinuations.

Other Potential Effects: Retatrutide’s glucagon component may transiently raise heart rate or slightly elevate liver enzymes, but no serious hepatotoxicity signals to date.

Reference: Retatrutide Phase 2: New England Journal of Medicine

4. CagriSema (Cagrilintide + Semaglutide Combo)

Profile: Cagrilintide alone can cause nausea and decreased appetite (amylin effect). In combination with semaglutide, GI symptoms remain the most common but are typically manageable.

No New Safety Signals: Trials thus far report no unexpected events beyond known GLP-1 and amylin effects.

Dropout Rates: Low single-digit percentages for GI reasons, thanks to careful titration schedules.

Reference: CagriSema Trial 2023 (REDEFINE program)

5. Survodutide (BI 456906) & Pemvidutide (Altimmune)

Mechanism: Both are GLP-1/glucagon co-agonists, which can intensify GI issues if escalated too quickly.

GI Effects: Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea remain the top adverse events.

Early Trial Dropouts: In Phase 2, ~10–25% of participants on higher doses sometimes discontinued, often due to GI intolerance. Sponsors now use slower titration to reduce early attrition.

Glucagon-Related Metabolic Changes: Possible transient hyperglycemia if glucagon activity outweighs GLP-1’s insulinotropic effect—usually mitigated by proper dosing.

References: Survodutide trial updates: Boehringer Ingelheim press release. Pemvidutide data: Altimmune investor presentation.

6. Oral GLP-1 Agonists (Orforglipron, Others)

Profile: Oral dosing still triggers classical GLP-1 side effects—nausea, etc.—but timing can differ (daily exposure vs. weekly peaks).

Discontinuation: In orforglipron’s Phase 2, ~10–17% of participants across doses stopped primarily for GI reasons.

Potential Advantages: No injection-site reactions, which can occur with injectable formulations.

Adherence Consideration: Daily pills may improve acceptance but some patients prefer once-weekly injections to avoid daily GI “peaks.”

Reference: Orforglipron Phase 2

7. Viking Therapeutics’ VK2735 (Subcutaneous and Oral)

Profile: Oral VK2735: Up to 8.2% mean weight loss at 28 days, sustained at Day 57 (8.3%). Subcutaneous VK2735: Achieved 14.7% mean weight loss by Week 13; 88% achieved ≥10% loss.

Discontinuation: Oral: Phase 1 reported mild adverse events (90%), no severe GI events; Phase 2a ongoing. Subcutaneous: Similar discontinuation to placebo (13% vs. 14%).

Potential Advantages: Oral: Avoids injection-site reactions; suitable for injection-averse patients. Subcutaneous: Sustained efficacy due to long half-life (170–250 hrs).

Adherence Consideration: Daily oral dosing may lead to transient GI symptoms; weekly injections may reduce this but carry injection-site risks.

Reference: VK2735 Phase 1 & 2 data.

8. Legacy Therapies

Phentermine/Topiramate (Qsymia): Side effects include dry mouth, insomnia, paresthesia, and potential mood/cognitive impact from topiramate. Blood pressure/hypertension precautions due to phentermine’s sympathomimetic properties.

Naltrexone/Bupropion (Contrave): High rates of nausea, headache, possible insomnia, and mild elevation in heart rate/blood pressure. Neuropsychiatric effects (e.g., anxiety) in some users.

Orlistat: Mainly gastrointestinal distress (oily stool, fecal urgency) if dietary fat content is high. Minimal systemic side effects otherwise.

C.) Rare but Notable Risks

Pancreatitis and Gallbladder Issues. GLP-1–based therapies carry a caution for acute pancreatitis, though the absolute risk increase is small. Rapid weight loss can predispose to gallstone formation, so cholelithiasis and cholecystitis are monitored in trials.

Thyroid C-Cell Tumors (Rodent Data). A “black box” warning for medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) risk exists for all GLP-1 receptor agonists, stemming from rodent studies. Human relevance appears minimal, but caution is advised in patients with personal/family history of MTC or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2.

Cardiac Effects (Heart Rate). Slight increases in resting heart rate (~2–5 beats/min) can be observed with most incretin therapies. Usually not clinically significant, but vigilance is needed in patients with baseline tachyarrhythmias.

Hypoglycemia Risk. GLP-1 RAs alone have low hypoglycemia risk unless combined with insulin or sulfonylureas. Glucagon agonism might raise glucose levels (counter to typical hypoglycemia risk), but in diabetic patients, adjustments to other antihyperglycemics may still be necessary.

READ: GLP-1 Receptor Agonists vs. Thyroid Cancer Risk (2025 Analysis)

D.) Managing Side Effects & Improving Adherence

Gradual Dose Escalation. Most protocols increase the drug dose every 2–4 weeks, helping mitigate nausea/vomiting.

Behavioral Modifications. Smaller, more frequent meals; avoidance of high-fat or greasy foods; adequate hydration.

Patient Education. Setting expectations around early GI symptoms and explaining they often subside within weeks can improve persistence.

Monitoring and Follow-Up. Regular check-ins during the first 3–6 months to address emerging side effects promptly.

E.) Overall Safety Outlook

Favorable Benefit-Risk. Despite GI effects, the benefit-risk profile of modern incretin-based therapies is widely regarded as positive:

Substantial, durable weight loss can reduce cardiometabolic complications.

Most adverse events are mild, transient, and manageable with titration.

Long-Term Data Accumulating. Several of these agents now have multi-year safety extensions (semaglutide, liraglutide), with no major red flags. For newer ones (tirzepatide, retatrutide, dual-agonists), Phase 3 and post-marketing surveillance will clarify any rare or cumulative risks. Early signals are encouraging.

IV. Composite Rankings (2025): Weight Loss Drugs (Tolerability & Efficacy)

While high efficacy is undeniably attractive, clinical decisions also hinge on tolerability, long-term safety, ease of administration, and dropout rates. A composite score attempts to integrate:

Magnitude of Weight Loss: How much total (and percent) weight reduction is achievable on average.

Safety Profile: Rate and severity of adverse events—particularly GI-related, but also any rare serious risks.

Real-World Adherence Potential: Practical considerations like injection frequency, dose escalation protocols, or daily-pill burden.

Sustainability: Whether weight loss plateaus or rebounds significantly, and how often patients discontinue therapy.

A higher composite ranking typically indicates “best-in-class” balance: strong weight reduction with moderate, manageable side effects and feasible dosing regimens.

A.) Elite Tier (Highest Composite Scores)

1. Tirzepatide (ZepBound, Lilly)

Efficacy: ~20% mean weight loss (sometimes exceeding 22–23% in extended follow-up).

Tolerability: GI events are common but generally moderate; discontinuation ~5–7%.

Administration: Once-weekly subcutaneous injection with a structured titration schedule.

Composite Rationale: As the most potent approved option and overall well-tolerated, tirzepatide stands at or near the top of current therapy. Post-marketing real-world data further supports its favorable risk-benefit ratio.

Reference: Tirzepatide Once Weekly for Obesity

2. Semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy, Novo Nordisk)

Efficacy: ~15% average weight loss (a subset >20%).

Safety/Tolerability: GI side effects prominent during titration, but only ~4–7% overall discontinuation. Long-term safety track record is robust.

Administration: Once-weekly subcutaneous injection; well-established in clinical practice.

Composite Rationale: Despite being outpaced by tirzepatide in efficacy, semaglutide’s proven track record, moderate side-effect burden, and extensive real-world experience keep it among the best choices for many patients.

3. Retatrutide (Eli Lilly, Triple Agonist) — Projected Ranking

Efficacy: Phase 2 data ~24% weight loss at 48 weeks (the highest reported).

Safety: GI events similar to other incretins; no major red flags so far but still under investigation in Phase 3.

Administration: Once-weekly injection, with a slow titration recommended.

Composite Rationale: If Phase 3 confirms these results without new safety concerns, retatrutide could surpass all currently approved agents in both efficacy and overall benefit. For now, it is not yet approved, so we list it as a projected top-tier therapy.

Reference: Unleashing the Power of Retatrutide

4. CagriSema (Semaglutide + Cagrilintide, Novo Nordisk) — Projected Ranking

Efficacy: Phase 2 data ~15–16% by 32 weeks; extended trials hitting ~20% for many.

Tolerability: GI side effects from both GLP-1 and amylin analog, but typically manageable with gradual up-titration.

Administration: Once-weekly co-formulation; still in Phase 3.

Composite Rationale: Combining amylin’s satiety effect with semaglutide’s proven appetite suppression may yield efficacy close to tirzepatide, with a tolerability profile akin to semaglutide alone. If approved (target ~2026), it could vie for a top spot.

B.) Mid Tier

1. Survodutide (BI 456906)

Efficacy: Up to ~15–19% in Phase 2, but dropout rates were higher initially (~20–25% in some arms).

Safety: GI side effects are dose-dependent. A slower titration may reduce discontinuations in Phase 3.

Composite Score: Potential to reach near-top-tier if Phase 3 confirms high efficacy with improved tolerability.

2. Pemvidutide (Altimmune)

Efficacy: ~15.6% at 48 weeks (Phase 2), plus favorable hepatic/lipid profiles.

Tolerability: Some GI challenges; needs meticulous titration.

Composite Score: Competitive vs. semaglutide-level weight loss, but overshadowed by tirzepatide’s 20%+ range. Could fill a niche in NASH/lean mass preservation.

3. Orforglipron (Eli Lilly, Oral GLP-1)

Efficacy: ~14–15% in mid-stage trials—on par with injectable semaglutide.

Safety/Tolerability: GI side effects fairly common (10–17% discontinuation at higher doses).

Administration: Daily oral pill (no injections).

Composite Score: Gains extra points for patient convenience (oral route). If Phase 3 data replicate these results and side effects remain moderate, many see it as a “needle-free Wegovy” alternative, ranking it high overall.

4. Viking Therapeutics’ VK2735

Efficacy: Subcutaneous form ~14.7% in ~13 weeks (Phase 2 short-duration); oral form ~8% in 28 days (Phase 1).

Safety: GI side effects typical of GLP-1/GIP combos, generally mild-mod with ~comparable dropout to placebo for the SC version.

Composite: Encouraging but early. If longer studies confirm durability/tolerability, VK2735 (SC or oral) could compete with orforglipron for an upper-mid tier spot.

C.) Low Tier

1. Phentermine/Topiramate (Qsymia)

Efficacy: ~9–10% average loss.

Side Effects: CNS effects (insomnia, mood changes), potential teratogenicity, BP concerns.

Composite: Although more potent than older single agents, it’s outclassed by modern GLP-1–based therapies in terms of net weight loss and overall tolerability profile.

2. Liraglutide (Saxenda)

Efficacy: ~8% mean reduction, daily injections.

Safety: Similar GI side effect profile to other GLP-1s but with more frequent injections.

Composite: Solid safety legacy but overshadowed by weekly semaglutide and now higher-efficacy dual agonists.

3. Naltrexone/Bupropion (Contrave)

Efficacy: 5–8% mean loss.

Side Effects: Nausea (~30%), potential mild psychiatric/cardiovascular effects from bupropion.

Composite: Low-mid range, used primarily if GLP-1 therapies are contraindicated or inaccessible.

4. Orlistat (Xenical)

Efficacy: ~5–7% mean reduction.

Tolerability: High incidence of “oily stools” and GI distress when dietary fat intake is not strictly moderated.

Composite: Minimal systemic risk, but the inconvenience of GI side effects and limited efficacy place it near the bottom.

5. Other Legacy Agents

Drugs like diethylpropion, older sympathomimetics (benzphetamine), or exenatide (short-acting) produce modest weight loss with less favorable dosing or side-effect profiles, so they generally rank lower in modern practice.

Note: Retatrutide and CagriSema remain investigational; final composite ranking awaits Phase 3 and regulatory evaluation. Similarly, orforglipron’s position depends on confirmation of Phase 2 results in larger studies. I would guess that Retatrutide will have more side effects due to higher GLP-1 potency… usually there are tradeoffs between efficacy and tolerability to some extent.

Clinical Implications of Composite Rankings

Patient-Centered Selection: Agents with very high efficacy but more complex GI side effects may suit those requiring maximal weight loss (e.g., severe obesity). Others with slightly lower efficacy but proven longer-term safety might be best for mild-to-moderate obesity or patients sensitive to GI events.

Future-Shaping Agents: Oral orforglipron could drastically expand uptake if real-world tolerability is acceptable. Triple-agonists like retatrutide may transform obesity treatment further, approaching surgical-level outcomes.

Insurance Coverage: As more high-performing therapies launch, cost and formulary decisions may hinge on these composite advantages—efficacy, tolerability, and net health-economic benefits.

V. Most Promising Weight Loss Drugs in Development (2025 Clinical Trials Pipeline)

A.) Late-Stage (Phase 3) Candidates Likely to Reach Approval Soon

Retatrutide (Eli Lilly) — Triple Agonist

Mechanism: Simultaneously activates GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon receptors, aiming to reduce appetite, boost insulin sensitivity, and enhance energy expenditure.

Key Results: Phase 2 trial published in NEJM showed ~24% mean weight loss at 48 weeks (highest reported thus far for a pharmacologic agent).

Outlook: Phase 3 trials have commenced. If safety signals remain clean, approval could come as early as 2026–2027. Many experts predict retatrutide may redefine top-tier efficacy for obesity treatment.

CagriSema (Semaglutide + Cagrilintide, Novo Nordisk)

Mechanism: Weekly fixed-dose combination of a GLP-1 receptor agonist (semaglutide) and a long-acting amylin analog (cagrilintide). Both reduce appetite and food intake via complementary pathways.

Key Results: Phase 2 data showed up to ~15–16% mean weight loss by week 32, with some patients reaching ≥20% by 68 weeks in extended trials.

Development Status: Phase 3 is ongoing (the REDEFINE program). Novo Nordisk projects a regulatory submission around 2026. If approved, CagriSema could match or exceed the efficacy of semaglutide alone and challenge dual agonists like tirzepatide.

Orforglipron (Eli Lilly) — Oral GLP-1 RA

Mechanism: A daily, non-peptide small-molecule agonist of the GLP-1 receptor, providing semaglutide-like appetite suppression without injections.

Key Results: Phase 2 data (36 weeks) showed up to ~14–15% average weight loss, near injectables’ levels. GI side effects (nausea, diarrhea) caused discontinuations of about 10–17%.

Outlook: Entered Phase 3 in 2023. If efficacy and tolerability hold, approval could come by 2026. This would be the first truly effective oral GLP-1 for obesity, appealing to patients who dislike needles.

Survodutide (BI 456906, Boehringer Ingelheim & Zealand Pharma)

Mechanism: Dual agonist of GLP-1 and glucagon receptors (similar to oxyntomodulin). Glucagon may further boost energy expenditure and reduce hepatic fat.

Key Results: Phase 2 data at 46 weeks: ~15–19% weight loss depending on titration success; dropouts mainly due to GI issues.

Status: BI is initiating Phase 3 trials. With improved dose-escalation protocols, they hope to reduce early GI-driven discontinuations. Potential approval ~2026–2027.

B.) Mid-Stage (Phase 2) Candidates Showing Strong Potential

Pemvidutide (Altimmune)

Mechanism: Another GLP-1 + glucagon dual agonist. Derived from oxyntomodulin analogs, targeting both appetite and fat oxidation pathways.

Key Results: Phase 2 MOMENTUM trial: ~15.6% mean reduction at 48 weeks on the highest dose, plus notable liver fat reduction and better lean-mass preservation.

Challenges: Altimmune is a smaller biotech, so funding large Phase 3 trials or partnering with a bigger pharma is critical. If pursued, likely approval could be around 2027–2028.

Maridebart Cafraglutide (MariTide, Amgen)

Mechanism: An investigational antibody-peptide conjugate that antagonizes GIP receptors while agonizing GLP-1—an opposite approach to tirzepatide’s GIP agonism.

Key Results: Phase 1 multiple-dose data suggested rapid, significant weight loss (~14–15% in just 12 weeks), and Amgen’s Phase 2 results (unpublished in detail, but hinted at robust further loss).

Next Steps: Potential transition to Phase 3 in 2024–2025. If monthly dosing is feasible, it may offer a convenience advantage. Approval timeline could be ~2027 or later.

Bimagrumab (Versanis/Lilly)

Mechanism: A myostatin/activin receptor blocker that enhances muscle mass while reducing fat mass. Not primarily a stand-alone obesity drug but intended to complement GLP-1 therapies.

Key Results: In earlier trials, bimagrumab monotherapy shifted body composition (reduced fat, increased lean mass) with mild net weight loss (~6%). Now being studied with semaglutide or tirzepatide to see if it can preserve or add muscle while achieving high fat loss.

Outlook: If successful, it could address a major gap—excess lean mass loss with potent weight-loss agents. Phase 2 combination trials are ongoing; full Phase 3 might start 2025+.

Viking Therapeutics’ VK2735 – Dual GLP-1/GIP

Mechanism: Similar dual incretin concept as tirzepatide, though earlier stage.

Efficacy: Subcutaneous version showed ~14.7% over 13 weeks (short trial); oral version ~8% in 28 days.

Next Steps: Longer Phase 2 expansions for both forms; potential Phase 3 start ~2025. Approval ~2027–2028 if data confirm durability.

C.) Other Emerging Strategies & Novel Mechanisms

RNA Therapeutics (Arrowhead, etc.)

Concept: RNAi-based approaches to knock down specific genes in adipose tissue (e.g., INHBE or ALK7) linked to fat accumulation.

Status: Early-stage (Phase 1/2). Potentially used as adjunct to powerful appetite suppressants.

Peripheral CB1 Antagonists

Concept: Block peripheral cannabinoid type 1 receptors to reduce lipogenesis and appetite signals, without central mood-related adverse effects that doomed rimonabant.

Players: Novo Nordisk acquired Inversago for a CB1 program; AstraZeneca also exploring.

Timeline: Phase 1 or early Phase 2 in 2025–2026. Potential synergy with GLP-1 to curb hunger from multiple pathways.

Mitochondrial Uncouplers (Rivus Pharma’s HU6)

Goal: Modestly increase energy expenditure by “uncoupling” oxidative phosphorylation, avoiding the dangerous hyperthermia risks of old DNP.

Status: Phase 2 in overweight individuals with heart failure; some data showed reduced visceral fat.

Potential: Could be used alongside appetite suppressants for a “dual approach” (eat less + burn more), but safety and dose control are critical.

Myostatin/Activin Inhibitors (Beyond Bimagrumab)

Examples: Regeneron’s trevogrumab, Roche’s anti-latent myostatin approaches.

Objective: Preserve or increase muscle while losing fat. Especially relevant for older adults or frailty risk.

Timeline: Most are in early Phase 1/2 for sarcopenic obesity or in combo with GLP-1.

Interpretation & Outlook

Dominant Players: Lilly (retatrutide, orforglipron) and Novo Nordisk (CagriSema, semaglutide combos) lead the late-stage pipeline.

New Challengers: Amgen, Boehringer, Viking, Altimmune each have unique multi-agonists or combination concepts aiming to exceed or match 15–20% efficacy.

Unmet Needs: Potential combos addressing muscle preservation (myostatin blockade) or energy expenditure (uncouplers) could become adjuncts, especially in severe obesity.

Timeline: By 2026–2027, multiple new approvals are likely, pushing average weight reductions closer to ~20–25% for more patients.

With so many late-stage contenders, the obesity treatment landscape will likely expand dramatically, offering greater customization (injection frequency, oral vs. injectable, synergy with NASH or muscle-sparing) over the next few years.

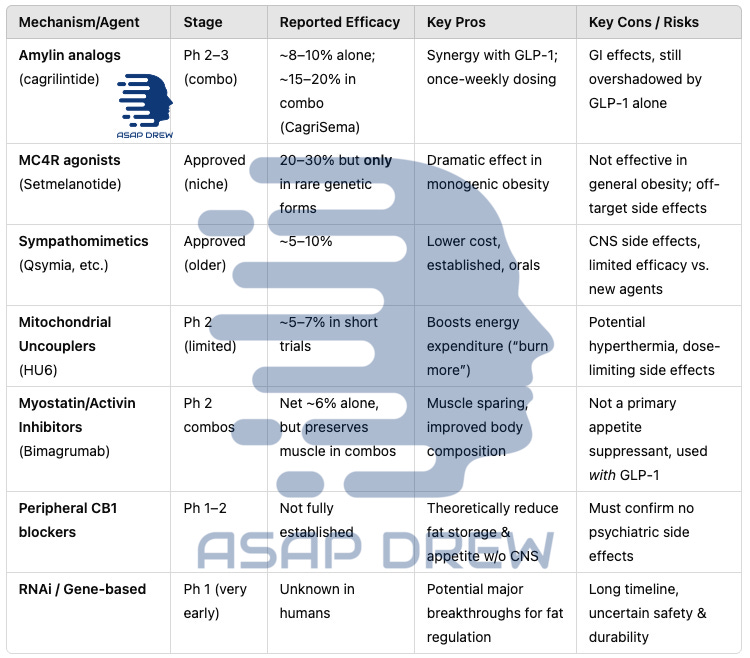

VI. Beyond GLP-1s: Alternative Mechanisms of Action for Weight Loss Drugs

While GLP-1 receptor agonists (and related multi-agonist variations) currently dominate the anti-obesity field, there are multiple other hormonal, metabolic, and molecular pathways under investigation. Some are meant to complement GLP-1 therapy, others to offer alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate incretin-based treatments.

A.) Amylin Analogues (Standalone and Combo)

Amylin is a satiety hormone co-secreted with insulin. Pramlintide (Symlin) is an amylin analog originally for diabetes that causes modest weight loss (~3–5%), but requires multiple daily injections.

A next-generation analog, Cagrilintide, is longer-acting (once-weekly) and being combined with semaglutide (as CagriSema) — this was already discussed.

Amylin agonists promote fullness and slow gastric emptying via the amylin/calcitonin receptor pathway, with potentially fewer GI side effects than GLP-1.

Cagrilintide alone led to significant weight loss (~8–10% in 26 weeks) in trials, and in combination (as noted) it greatly boosted efficacy to ~16% in 32 weeks.

Amylin analogs can cause nausea (pramlintide’s main side effect), but cagrilintide’s weekly dosing seems well-tolerated, and combining it with GLP-1 may allow lower doses of each, improving GI tolerability. This approach – hitting multiple satiety hormones (e.g. GLP-1 + amylin) – is emerging as a powerful strategy.

Pramlintide (Symlin) – Older Prototype

Mechanism: Amylin, co-secreted with insulin, promotes satiety and slows gastric emptying.

Efficacy: Modest (~3–5% weight loss) when given multiple times daily.

Limitations: High injection frequency and relatively modest weight reduction prevented widespread adoption for obesity.

Cagrilintide (Novo Nordisk)

Next-Gen: A long-acting amylin analog, weekly dosing.

Efficacy (Monotherapy): ~8–10% mean loss at 26 weeks in Phase 2 obesity trials.

Amylin + GLP-1 Synergy: Combined with semaglutide in the emerging CagriSema product has produced 15–20% weight loss, reflecting additive or synergistic effects on appetite.

Takeaway: Amylin analogs alone may lag behind GLP-1 in potency, but combination regimens (GLP-1 + amylin) show substantial synergy and rank among the most promising future therapies.

B.) GDF-15 (Growth Differentiation Factor 15) Pathway

Physiologic Role: GDF-15 is a stress-induced cytokine that, via binding to the GFRAL receptor in the hindbrain, strongly suppresses appetite. In rodents, GDF-15 can induce significant weight loss.

Clinical Attempts: Novartis/Merck tested GDF-15 analogs or agonists in Phase 1/2. Early excitement about robust rodent data tempered after human trials showed mixed efficacy (less appetite suppression than expected, plus dose-limiting nausea). No leading GDF-15 candidate remains in advanced trials for common obesity as of 2025.

Challenges: Tolerance may develop rapidly, and side effects (persistent nausea) limit how high one can dose. GDF-15 analogs could re-emerge in combination therapies if scientists solve the tolerability puzzle.

Takeaway: Although theoretically powerful, GDF-15 agonism has not yet delivered strong, sustained weight loss in humans. Current interest has shifted to multi-agonist gut hormones.

C.) Melanocortin-4 Receptor (MC4R) Agonism

The MC4 receptor in the hypothalamus is a key regulator of hunger and energy expenditure. Setmelanotide (Imcivree), an MC4R agonist, is approved for rare genetic obesity syndromes (POMC/LEPR deficiencies, Bardet-Biedl syndrome).

It can produce dramatic weight loss (≥10% or more) in those specific conditions by restoring a broken satiety circuit. However, in general obesity its role is limited – MC4 activation in people with intact pathways causes significant side effects (e.g. skin hyperpigmentation, nausea, and especially severe transient erections in men due to melanocortin effects).

Thus, setmelanotide is reserved for genetic cases and is not pursued for common obesity. Nonetheless, it exemplifies targeting the brain’s appetite center directly. Ongoing research is exploring safer ways to modulate this melanocortin pathway or downstream signals for broader use.

Setmelanotide (Imcivree)

Mechanism: Targets MC4 receptors in the hypothalamus, critical for satiety.

Efficacy: Dramatic weight loss (>20%) in individuals with rare genetic MC4R pathway deficiencies (e.g., POMC deficiency, Bardet-Biedl syndrome).

In Common Obesity: Minimal benefit if the MC4R pathway is intact; off-target issues (hyperpigmentation, sexual arousal effects) are also a concern.

Future Outlook: MC4R agonism remains viable for certain monogenic forms of obesity. Unlikely to be widely adopted for general obesity unless next-gen molecules address these off-target effects and leptin resistance.

D.) Sympathomimetics & CNS Appetite Modulators

Traditional weight-loss drugs targeted the brain’s appetite and reward circuits. Examples include phentermine (a stimulant that suppresses appetite) and topiramate (an anti-seizure medication that causes appetite reduction).

The combination phentermine/topiramate (Qsymia) is an approved therapy yielding ~8–10% weight loss. Similarly, bupropion/naltrexone (Contrave) targets dopamine reward and opioid feedback, resulting in ~5% weight loss.

These older combinations can be effective for some, but their side effects (insomnia, dry mouth, mood changes for phentermine; or nausea, headache for bupropion/naltrexone) and moderate efficacy make them less competitive now that GLP-1 agents can achieve >15%.

They remain options particularly when GLP-1s are contraindicated or unaffordable. Researchers continue to look at novel CNS targets – e.g. serotonin 5-HT2C agonists (like the now-withdrawn lorcaserin) and histamine H3 antagonists – but none have yet matched the efficacy of incretin therapies without unacceptable adverse effects.

A notable new CNS-target approach is CB1 cannabinoid receptor blockade: Rimonabant (a central CB1 inverse agonist) was very effective (~5–6 kg loss) but caused depression/suicidality, leading to withdrawal.

Now, peripherally-restricted CB1 blockers (e.g. INV-202 from Inversago, acquired by Novo Nordisk) are in early trials to harness weight loss and metabolic benefits of CB1 blockade without crossing the blood–brain barrier.

If successful, such agents could reduce appetite and improve metabolism via peripheral CB1 receptors (in fat, liver, GI tract) while avoiding the psychiatric side effects.

Phentermine (Short-Term Use): Oldest approved appetite suppressant in the U.S., typically prescribed for a few months.

Efficacy: ~5–7% short-term weight reduction.

Side Effects: Insomnia, tachycardia, potential BP elevation, anxiety—limits long-term use.

Phentermine/Topiramate (Qsymia): A combination approach to yield ~9–10% at 1 year. Still overshadowed by ~15%+ from newer therapies.

Bupropion/Naltrexone (Contrave): Influences reward pathways (dopamine, opioid) to reduce food cravings, ~5–8% mean loss. Moderate GI and CNS side effects, mild BP/HR changes.

Future CNS Targets:

CB1 Receptor Antagonists (rimonabant-like) but peripherally restricted to avoid psychiatric issues.

H3 Histamine Receptor, 5-HT Receptors, etc. are under sporadic exploration but have not matched GLP-1’s potency or safety to date.

Takeaway: While these older CNS-centric drugs helped define pharmacotherapy for obesity, they have been supplanted by incretin-based therapies’ superior efficacy and more tolerable side-effect profiles.

E.) Mitochondrial Uncouplers (Thermogenic Fat Burners)

A fundamentally different approach is to increase energy expenditure instead of (or in addition to) suppressing appetite. Mitochondrial uncoupling makes cells burn fuel inefficiently as heat.

The infamous chemical DNP (2,4-dinitrophenol) from the 1930s caused substantial weight loss by uncoupling respiration, but was banned due to fatal hyperthermia. Now, companies like Rivus Pharmaceuticals are revisiting this mechanism with controllable “mild” uncouplers.

Rivus’s compound HU6 is a “Controlled Metabolic Accelerator” that selectively increases fat oxidation by ~30% without the dangerous overheating seen with DNP. In a Phase 2a trial in obese patients with heart failure, HU6 significantly reduced body fat (especially visceral fat) while preserving lean muscle. HU6 is taken orally once daily.

Safety: So far, HU6 trials have shown it can raise metabolic rate and fat burn without serious adverse effects (no severe fevers, etc.), though mild increases in resting heart rate and warmth can occur as expected from higher energy expenditure.

If proven safe long-term, metabolic uncouplers could be combined with appetite suppressants (addressing both sides of the calorie equation). This “burn more calories” approach is appealing because it supports muscle mass (the body uses more fat for fuel instead of breaking down muscle).

HU6 isn’t yet being tested purely for obesity, but its success in metabolic trials suggests a new class of fat-targeting weight loss drugs may emerge.

Concept: Mild uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation so cells consume more calories as heat—akin to the mechanism behind the old (and dangerous) DNP.

Rivus Pharmaceuticals’ HU6: A “controlled metabolic accelerator” in Phase 2 for obesity with heart failure; early data show reduced visceral fat and modest (5–7%) weight loss. Safety is the main concern: avoid severe hyperthermia or organ damage that historically plagued uncouplers.

Combination Therapy Potential: If uncouplers prove safe, combining with potent appetite suppressants (like GLP-1 RA) may deliver a dual-pronged approach: eat less + burn more.

Takeaway: Uncouplers are an intriguing “energy expenditure” strategy. Long-term feasibility depends on precise dosing and tight safety margins.

F.) Myostatin/Activin Inhibitors (Preserving Muscle Mass)

A novel goal in obesity pharmacotherapy is enhancing body composition – i.e. maximizing fat loss while minimizing muscle loss. Typically, ~25–35% of weight lost with diet or GLP-1 drugs is lean mass (muscle), which could be detrimental, especially in older patients. Drugs that block myostatin or activin (muscle growth inhibitors) can spur muscle gain or preservation during weight loss.

For example, Bimagrumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting activin type II receptors, was shown to cause fat loss while increasing muscle mass. In a previous trial, bimagrumab led to a ~21% reduction in body fat and a 3% gain in lean mass over 48 weeks (net ~6% weight loss, but a healthier composition) in overweight diabetics.

Seeing the potential, Lilly acquired Versanis Bio’s bimagrumab in 2023. Now Lilly is testing bimagrumab + semaglutide together – aiming for the high fat loss of GLP-1 plus muscle retention of bimagrumab. Early-phase trials will measure changes in fat mass and lean body mass rather than just scale weight.

Similarly, companies like Regeneron (with trevogrumab, an anti-myostatin antibody) and Roche (with an anti-latent myostatin, RG6237) are running studies combining those agents with GLP-1 therapy.

Safety considerations: Myostatin inhibitors can cause increased muscle volume and possibly joint pains or minor elevations in liver enzymes, but generally have been well tolerated in trials for muscle diseases.

The main question is efficacy – whether preserving/gaining muscle translates to meaningful functional benefits (e.g. strength, mobility) and sustained higher metabolic rate during weight loss. Initial results are encouraging: one trial found adding a myostatin blocker (Regeneron’s) to Wegovy cut lean mass loss by ~71%.

These agents on their own may not reduce weight dramatically (they primarily shift body composition), so they’re likely to be adjuncts to potent weight-loss drugs in the future. By addressing the muscle loss “side effect” of weight loss, they could improve overall outcomes and patient frailty, especially in older or sarcopenic obese individuals

Mechanism: Myostatin and activin limit muscle growth. Blocking them can increase or preserve muscle, potentially preventing the 25–35% lean mass loss observed with many diet or drug-induced weight losses.

Leading Example: Bimagrumab (Now owned by Eli Lilly): In T2D patients, bimagrumab reduced body fat while increasing lean mass, resulting in net modest weight loss (~6%).

Combo Trials: Pairing bimagrumab (muscle-sparing) with a high-efficacy GLP-1 or dual agonist to achieve deeper fat loss without compromising strength.

Others: Regeneron, Roche, and smaller biotechs also have myostatin/activin antibodies or traps in early phases.

Takeaway: These agents might become key adjuncts to potent weight-loss drugs, especially for older adults where preserving lean mass is essential.

G.) FGF21 Analogues & Other Hormone Targets

The obesity field is revisiting many old targets with new technology.

Some examples: Leptin sensitizers (e.g. celastrol, an herb-derived molecule, in preclinical studies to restore leptin responsiveness), FGF21 analogs (hormones that increase metabolism and insulin sensitivity – e.g. Pfizer’s PF-089, 89bio’s pegozafermin – initially for NASH but they also reduce body weight ~5-7%), thyroid hormone receptor-β agonists (like resmetirom, which in NASH trials caused ~8% weight loss as a side effect by boosting metabolic rate).

PYY (Peptide YY) and OXM (oxyntomodulin) analogs are in early development or being combined with GLP-1. For example, intranasal PYY was tried but had limited effect. Some newer poly-agonists include PYY as a component with GLP-1/GIP.

There is also interest in combinations of these – for example, merging a thyroid mimic with a GLP-1 might amplify calorie burning and weight loss (though careful monitoring of heart effects would be needed).

SARM (selective androgen receptor modulators) like enobosarm (Veru Inc.) are being tested alongside GLP-1 to see if they preserve muscle and bone during weight loss.

FGF21 (Fibroblast Growth Factor 21)

Regulates insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism.

FGF21 analogues (e.g., efruxifermin, pegozafermin) developed mainly for NASH; they show moderate weight loss (~5–10%).

Future combos with GLP-1 or triple agonists might amplify fat reduction.

Leptin, PYY, Oxyntomodulin

Past attempts at leptin therapy in common obesity failed due to leptin resistance.

PYY and OXM analogs now appear in dual/triple hormone combos (like GLP-1 + PYY).

Intranasal or oral forms had limited success alone.

SGLT2 Inhibitors (Diabetes Cross-Use)

Empagliflozin, dapagliflozin cause mild weight loss (2–3%), mostly in type 2 diabetes populations. They remain an adjunct, not a front-line anti-obesity monotherapy.

Takeaway: Many hormones beyond GLP-1 can modestly affect appetite/metabolism, but none have matched GLP-1’s potency except when combined in next-gen multi-agonists.

H.) Gene & RNA-Based Interventions

RNA-based therapies are entering the arena: Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals has RNA interference drugs targeting genes in fat tissue (e.g. INHBE, ALK7) to reduce fat storage signals.

These might be injected infrequently (monthly or quarterly) to tweak metabolic pathways in adipose tissue. While most of these are in early stages, they underscore a broad “whole-system” attack on obesity – not just appetite, but also how calories are burned and how body composition is regulated.

Arrowhead’s two obesity-targeted RNAi drugs (ARO-ANCHOR, now ARO-ALK7 and ARO-INHBE) aim to reduce signals that cause fat storage. They should enter Phase 1 in 2025.

If they show even a few percent weight loss or improved metabolic markers, Arrowhead may partner with Lilly or Novo (indeed, one plan is to try ARO-INHBE with tirzepatide).

The likelihood of approval is far off (~2028+), but conceptually these could become injectable adjuncts (e.g. an infrequent shot to augment other drugs).

And while not in trials yet, there’s also academic exploration of CRISPR-based therapies to turn white fat into brown fat or to knock out genes like PCSK1 in adipose tissue to increase energy expenditure — or directly edit GLP-1.

This is far from clinical use, but underscores how future obesity treatment might even include one-time interventions if safety allows.

RNA Interference (RNAi)

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals is exploring adipose-specific knockdowns of genes that promote fat accumulation. Phase 1/2 data are pending.

Potential synergy: Use an RNAi agent to reduce fat storage signals while GLP-1 or amylin reduces intake.

Gene Editing

Preclinical CRISPR-based attempts to convert white fat to brown fat or alter hypothalamic satiety pathways.

Practical, clinical use is still distant (beyond 2028).

Takeaway: These cutting-edge genetic approaches could be revolutionary but remain early-stage, years away from large-scale obesity treatment approvals.

Non-GLP-1 Weight Loss Drugs in Development (2025)

Amylin combos, myostatin blockers, and uncouplers stand out as potentially significant adjuncts to existing incretins or multi-agonists, enhancing or fine-tuning outcomes (e.g., muscle preservation, increased energy burn).

CNS-targeting drugs (sympathomimetics, naltrexone/bupropion) still have a role but are overshadowed by the efficacy and safety of GLP-1–based regimens.

Highly innovative areas (RNAi, gene editing) remain speculative but underscore the ongoing push to find new angles on chronic weight regulation.

Bottom Line: In the near and medium term, the core of obesity pharmacotherapy remains incretin-based (targeting GLP-1/GIP). Alternative mechanisms mostly show potential as complementary strategies or niche solutions where GLP-1 pathways are inadequate or contraindicated. Longer term, combination therapies that tackle both appetite and energy expenditure—and address body composition—may define the next wave of obesity care.

Note: There are more that I didn’t mention in this write-up including gastric hydrogels.

VII. Development Pipeline, Clinical Trials, Regulatory Path (2025)

As the obesity pharmacotherapy landscape rapidly evolves, several late-stage candidates could reach the market within the next 1–3 years, while mid-stage contenders continue to refine dosing and demonstrate longer-term safety.

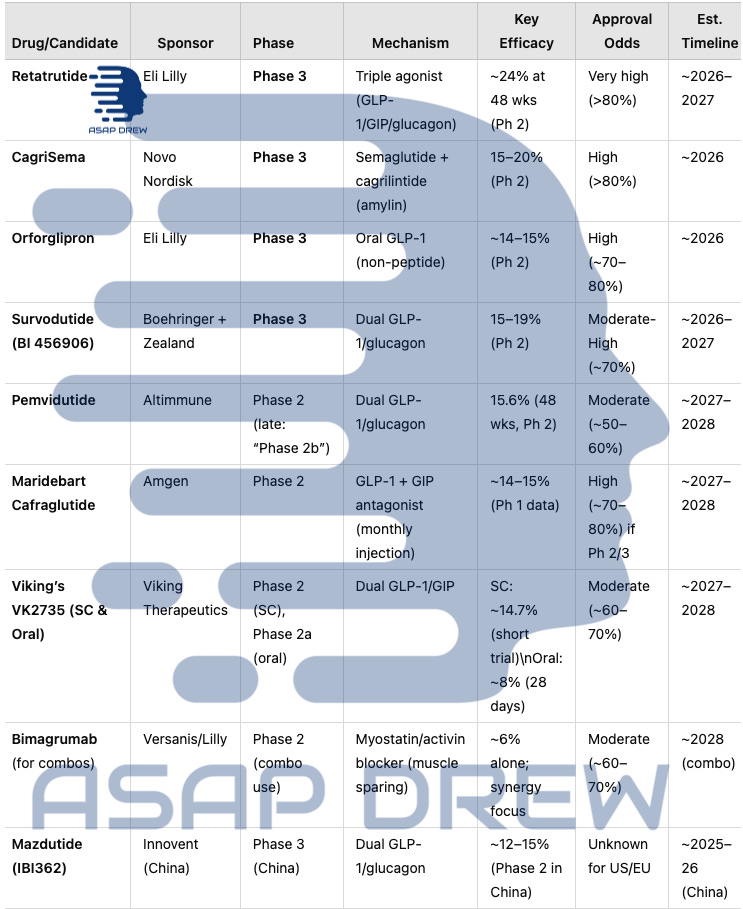

A.) Late & Mid-Stage Obesity Pipeline (2025)

B.) Phase & Regulatory Highlights

Retatrutide (Eli Lilly): In active Phase 3 after record-setting ~24% average loss in Phase 2. Launch possible ~2026–2027 if safety remains solid.

CagriSema (Novo Nordisk): Phase 3 (REDEFINE) continues; Phase 2 suggested up to ~15–20% weight loss, short of 25% initially hoped. Potential 2026 filing.

Orforglipron (Lilly): The leading oral GLP-1 candidate in late-stage; if Phase 3 mirrors ~14–15% from Phase 2, approval could come by ~2026.

Survodutide (BI 456906): FDA Breakthrough Therapy (Oct 2024) for MASH/obesity. Phase 3 aims to refine dose escalation to reduce dropout (~20–25% in Phase 2).

Pemvidutide (Altimmune): Completed Phase 2b enrollment for both obesity and MASH. ~15.6% at 48 weeks in Phase 2. Potential Phase 3 by 2026, approval ~2027–2028 if partnered.

Maridebart Cafraglutide (Amgen): Phase 2 ongoing for this monthly injection approach. If efficacy meets ~14–15% or more in longer trials, Phase 3 could start ~2024–25, leading to a 2027–2028 launch.

Viking’s VK2735: Subcutaneous form in Phase 2 after short-trial data showing ~14.7% loss; an oral version in Phase 2a with ~8% 28-day results. Both forms might converge on Phase 3 in 2025, eyeing a 2027–2028 approval if results confirm durability.

Bimagrumab (Muscle-Sparing Add-on): Not a primary obesity drug; improves body composition by blocking myostatin/activin. Likely used in combo with GLP-1 or dual agonists to retain lean mass. Phase 2 combos ongoing.

Mazdutide (IBI362): Phase 3 in China; ~12–15% weight loss in local Phase 2. Western timeline unknown, but Chinese approval possible by 2025–26.

C.) Regulatory Trends & Fast-Track

Accelerated Pathways: FDA “Fast Track” or “Breakthrough” statuses become more common for agents showing ≥10–15% weight loss with favorable safety.

Global Variation: China fast-tracks local dual agonists like mazdutide. Europe often aligns with FDA but can request extra real-world safety monitoring.

Post-Marketing: Requirements include cardiovascular outcomes studies, especially for novel multi-agonists or new oral mechanisms.

D.) Comparison to Marketed Therapies

Retatrutide vs. Tirzepatide: If Phase 3 upholds ~24%, retatrutide might surpass tirzepatide’s ~20%.

CagriSema vs. Semaglutide: Combo with amylin analog may yield ~15–20% vs. ~15% for semaglutide alone.

Orforglipron / VK2735 (Oral): Both aim to match or approach ~15% injection-level results, potentially broadening uptake among injection-averse patients.

E.) Timeline Overview (2025–2027)

2025: Phase 3 readouts for retatrutide, orforglipron, and possibly CagriSema. Survodutide to finalize Phase 3 recruitment. Viking’s VK2735 subcutaneous likely completes Phase 2; oral transitions to Phase 2b.

2026: Multiple approvals probable (CagriSema, orforglipron, maybe Survodutide) if data confirm ~15–20% efficacy with tolerable GI profiles. Retatrutide may file late 2026 if Phase 3 is robust.

2027–2028: Retatrutide, pemvidutide, Maridebart Cafraglutide, and VK2735 subcutaneous/oral could finalize pivotal trials, further increasing the 20–25% efficacy bracket.

Takeaways:

The obesity pipeline remains crowded yet brimming with innovations—from triple agonists (retatrutide) to oral incretins (orforglipron, VK2735) and synergy combos (bimagrumab).

With multiple Phase 3 readouts looming, new approvals from 2025–2027 are expected to reshape obesity care, potentially enabling consistent 20–25% weight loss for many patients without surgery.

The race among major pharma (Lilly, Novo, Boehringer) and emerging biotechs (Altimmune, Viking, etc.) ensures continual progress, with each candidate targeting distinct patient preferences (oral vs. injectable, monthly vs. daily) and comorbidity benefits (NASH, muscle preservation).

VIII. Obesity Market Outlook & Competitive Landscape (Weight Loss Drugs)

As multiple high-efficacy obesity drugs approach or enter the market, the global landscape for weight-loss pharmacotherapy is rapidly expanding. Once considered a niche or “lifestyle” segment, obesity medication sales are now projected to reach $100–150+ billion by 2030.

This growth is fueled by (1) unprecedented efficacy, (2) broader recognition of obesity as a chronic disease, and (3) improving reimbursement frameworks.

A.) Estimated Market Size and Growth Drivers

Surging Demand

Clinical Demand: Millions of adults with obesity (BMI ≥30) or overweight (BMI ≥27 with comorbidities) are seeking medical alternatives to surgery.

Early Intervention: Intensifying interest in using pharmacotherapy before BMI escalates—preventing severe obesity and associated complications like type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Efficacy Threshold

Agents achieving ≥15% weight reduction are viewed as clinically meaningful. Now with tirzepatide/retatrutide approaching 20–25%, more patients and payers see these as transformative.

The strong link between weight loss and cardiometabolic risk reduction (fewer heart attacks, improved glucose control) encourages policymakers to consider coverage expansions.

Insurance Coverage and Policy Shifts

In the U.S., potential legislative changes like the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act could expand Medicare coverage for obesity drugs.

In Europe, historically conservative reimbursement agencies are becoming more receptive, given compelling health economics data (e.g., decreased need for insulin, reduced hospitalizations for obesity-related conditions).

Bottom Line: Analysts at major financial institutions (Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, etc.) foresee double-digit annual growth for at least a decade, propelled by new approvals and rising payer acceptance.

B.) Key Players & Competition

Eli Lilly

Approved: Tirzepatide (~20% efficacy), shaping the market.

Pipeline: Retatrutide (Phase 3, ~24%), orforglipron (oral GLP-1, Phase 3).

Strategy: Broad portfolio (weekly injection, triple agonist, oral). Could dominate multiple segments if new approvals succeed.

Novo Nordisk

Approved: Semaglutide (Wegovy), ~15% loss, widely used.

Pipeline: CagriSema (~15–20% Phase 2) in Phase 3, plus oral semaglutide expansions and amylin/CB1 research.

Core Strength: Experience in manufacturing and global scale, historically strong in diabetes/metabolic.

Boehringer Ingelheim & Zealand Pharma

Survodutide: 15–19% (Phase 2), now in Phase 3. Breakthrough designation for MASH highlights big potential.

Capability: Substantial R&D resources, but limited obesity track record compared to Novo/Lilly.

Amgen

Maridebart Cafraglutide (MariTide): Phase 2, monthly injection concept (14–15% short Phase 1 data).

Leverage: Biologic manufacturing expertise; new to obesity but aiming for a once-monthly advantage.

Altimmune

Pemvidutide: ~16% weight loss (Phase 2b). Focus on obesity + NASH synergy.

Small Player: Possibly seeking a co-development partner for Phase 3 financing.

Viking Therapeutics

VK2735: Subcutaneous (Phase 2) ~14.7% short-trial result, plus oral version.

Approach: Dual GLP-1/GIP, paralleling tirzepatide. Needs robust Phase 3 data to compete with big pharma offerings.

C.) Differentiators in a Crowded Market

Efficacy & Safety

Retatrutide’s ~24% sets a new bar. Others near ~15–20%. Minimizing GI dropouts remains crucial.

Comorbidity benefits (e.g., hepatic or muscle preservation) can sway prescribers, especially in specialized populations (NASH, sarcopenic obesity).

Mode of Delivery & Dosing Frequency

Oral solutions (orforglipron, oral VK2735) could open first-line usage, appealing to injection-averse patients.

Monthly dosing (Amgen) might attract those preferring fewer injections.

Cost & Reimbursement

Competition among multiple advanced agents may prompt some price moderation or bigger rebates.

Formulary decisions often favor a small subset of covered drugs unless multiple demonstrate strong value.

Combination & Adjunct Strategies

Pairing muscle-sparing (bimagrumab) or “energy expenditure” (mild uncouplers) with potent appetite suppressants might yield synergy for severe cases.

Tiered approaches: mild obesity with older/cheaper meds, severe obesity with top-tier multi-agonists.

D) Potential Market Scenarios by 2027

Scenario A: Lilly/Novo Duopoly Continues: Retatrutide, tirzepatide, orforglipron (Lilly) + semaglutide, CagriSema (Novo) remain top. Others (BI, Amgen) capture single-digit shares without a strong differentiator.

Scenario B: Multiniche Distribution: Survodutide or Amgen’s monthly injection find a convenience niche. Altimmune or Viking establish smaller but profitable segments (e.g., those wanting injection synergy or better GI profiles). Myostatin combos co-labeled for muscle-frail populations.

Scenario C: Oral Game-Changer: If orforglipron or Viking’s oral VK2735 achieve consistent ~15–17% with mild side effects, they could surpass injectables in first-line prescribing for moderate obesity, especially in primary care.

Scenario D: “Medical Bariatric Equivalence”: Retatrutide’s ~24% or combos push average losses close to 25–30%—rivaling surgery. Broad coverage and acceptance could lead to widespread usage, overshadowing older meds and even reducing surgical rates.

E.) Strategic Implications

Clinicians: Gain a broad range of agents; must weigh patient preference (oral vs. injectable), efficacy vs. side effects, cost, and comorbidities.

Payers/Insurers: Face rising demand. Might restrict to a top 1–2 advanced agents per formulary or require step therapy (e.g., Wegovy or cheaper GLP-1 before a multi-agonist).

Patients: Benefit from more potent, diverse options, but out-of-pocket costs and insurance approval remain barriers.

Pharma/Biotech: Ongoing competition drives innovation in dosing frequency, tolerability, combination regimens. Partnerships or acquisitions among smaller companies (Altimmune, Viking) are likely.

F.) Long-Term Outlook

Continued Innovation: Beyond 2027, triple agonists, muscle-sparing combos, and advanced orals may make 20–25% weight loss routine.

Preventive Use: Guidelines might shift to earlier pharmacologic intervention at BMI 27–30 to avert severe obesity.

Patent Cliff & Biosimilars: By the mid-2030s, older GLP-1 molecules (liraglutide, semaglutide) could face generic competition, broadening access but also increasing price pressure.

Overall: Obesity therapies could rank among the top-selling drug classes globally, mirroring the impact of statins in cardiovascular disease 20 years ago.

Overall: Market prospects for obesity pharmacotherapy remain extraordinarily strong, led by big pharma’s multi-agonist expansions and new oral formulations. With ~2 billion overweight/obese worldwide, the potential for multi-billion dollar revenues is immense—though differentiation on efficacy, tolerability, convenience, and cost will ultimately shape each agent’s market share.

Final Thoughts: Obesity vs. Weight Loss Drugs (2025)

Obesity is more treatable than ever before… if you’re obese in 2025, a weight loss drug or combo will likely help a lot (assuming no issues with tolerability and/or contraindications).

Major pharmas (Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk) continue to expand manufacturing and pipelines, while new players (Amgen, Boehringer, Viking, Altimmune) challenge the incumbents through novel dosing, combination strategies, or synergy with other metabolic benefits.

Over the next 2–5 years, I’d expect:

Multiple new approvals with 15–25% average weight loss,

Growing acceptance of long-term medication for BMI ≥27–30 in at-risk individuals,

Broadened insurance coverage as real-world data confirm health cost savings,

Further intensification of research into advanced multi-target or synergy therapies.

I also expect to see many formerly fat people (who never were able to lose weight in the past) suddenly appearing thin. If you aren’t sure whether someone is on these drugs… you don’t really need to ask — they probably won’t tell you. Just assume they are if they went many years with no weight loss and are suddenly thinner.

And there’s nothing wrong with taking these. Sure it’s a biological “cheat code” and there could be negative repercussions… but they might also be superior to going without (even for those who are just overweight — not obese).

If you want to use these drugs and don’t have good insurance, you can probably get them cheaper in other countries OR use a compounding pharmacy OR “peptide” seller and mix with bacteriostatic water, etc. (not going to explain this, but it’s something to consider if you’re cost-conscious)… generics are 8-10 years away for drugs like semaglutide.

If you want the real-deal and don’t want to take risks, ask your doc for an Rx. Know the risks though… I may write up a post of what tests to get done pre-treatment and during treatment to minimize risk of adverse reactions (e.g. thyroid cancer from GLP-1s).

Assuming big pharma/biotech and the U.S. government (slash regulations) gets their shit together — we should have some good obesity vaccines and/or cures (gene edits) in the future (e.g. 2030-2050).